Ashley Solomon is a very succesful flute and recorder player, director of renowned ensembles and Professor at the Royal College of Music in London. In 1991 he won the prestigious Moeck International Recorder Competition in London, which was crucial for his further musical career. In the same year he founded ensemble Florilegium and they recorded many CDs for the Channel Classics. For this recording company he has also recorded many successful solo projects such as the recording of the complete Bach flute sonatas which was awarded by the Gramophone Magazine in 2017. In 2005 he founded the orchestra and choir in Bolivia and together they are helping to promote baroque music from the mission archives. In the past Ashley Solomon together with Florilegium regularly visited the Czech Republic, particularly early music courses in Bechyně and Prachatice, where they indelibly influenced young generation of talented musicians..

Please, can you tell us about your musical beginnings? Were there any musicians in your family? Was the recorder or flute your favourite choice?

From a very early age I apparently loved to sing and rather embarrassingly, dance. My parents for years spoke about me at the age of 2 standing on the toy chest we had a home holding the toy hoover as a microphone and singing into it!

My mother was a concert pianist, and I grew up with music everywhere. I have an older sister and two younger brothers and luckily, we had two Bechstein pianos – an upright and a grand in separate parts of the house. As we all played the piano, it could be quite competitive to actually schedule time on the instrument, so we kept a timetable for practise. I started lessons on the piano from the age of 6 and by 8 I also started to have lessons on the recorder, which I loved. I found it such a natural extension of the voice and reading just one line of music as opposed to two with the piano felt quite straightforward. I felt very satisfied and loved studying both instruments equally. That was until my older sister started to have modern flute lessons. At this stage she was a Junior Exhibitioner at the Royal Academy of Music and we all knew she was going to be a professional musician. She certainly practised much more than the rest of us!

I was very jealous of her modern flute when she started and was desperate to play, but my parents decided that I would have to wait a year until I started secondary school at the age of 11. Being the cheeky sort of child that I was, I started going into my sister’s room when she was out, putting the flute together and playing along to her James Galway recordings by ear, making up fingerings and struggling with the mechanics of the flute. To be honest I think even then I made a reasonable sound. After all it was just like blowing across the top of a bottle which I did all the time. One Sunday when I was feeling particularly brave, I came downstairs for the family lunch with her flute tucked behind my back and announced that I wanted to perform something for everyone. I explained that I would only do this if nobody got angry with me until I had finished!! I then played my version of Annie’s Song that I had learned from the James Galway record. There was no stopping me after that and I started having proper flute lessons within a few weeks, six months before starting secondary school.

Do you have any special moments or favourite teachers in your musical studies? Did you meet teachers who influenced your musical future and how?

My first flute teacher was a lovely elderly lady who seemed ancient to me at the time and yet the flute sounded so inspiring when she played in lessons. She certainly helped to mould my musical identity from the ages of 10-16. By then I was enjoying the piano at school but not seriously enough to think about following my sister and I had also been teaching myself the recorder since my first teacher moved away from the area when I was 13. It seems ridiculous now to think that I was just playing the recorder for fun for nearly 3 years, working my way through lots of baroque repertoire for my own pleasure. When I was 16 I entered a local music competition and the recorder class was adjudicated by Dr Carl Dolmetsch. I won this competition in the open category and afterwards Dr Carl asked who my teacher was. I had to admit rather embarrassingly that I was teaching myself and he then offered to be my teacher. So once a month I would take the train from London down to Haslemere and he would collect me from the station with his accompanist the wonderful Joseph Saxby, and I would have a very long lesson with him, often from 2pm until around 5pm when his housekeeper Greta Matthews would interrupt the lesson by offering us tea and crumpets before I returned on the 6pm train. His stories and anecdotes were so inspiring for a young 16-year-old and I continued having these lessons with him for 2 years before I auditioned for the Royal Academy of Music. I was allowed to look around his library which was a huge honour as almost nobody was allowed access, and got to know the family very well, all of whom were musicians. Before starting at the RAM I also performed with the Dolmetsch Consort (there are some very old and “interesting” recordings out there!!) in the Haslemere Festival and then started teaching on their recorder course in the summer. Carl was certainly an inspiration at the time and his experience and stories made for many pleasant hours, but I was aware even then that the family idea of early music, instrument making and editing baroque music was not necessarily the one I wanted to follow when I started my serious studies. It gave me some perspective, but I wanted a more authentic experience of historical performance which I knew would happen once I commenced my studies in London.

I auditioned from the RAM in 1986 as a joint principal recorder and modern flute student. Back then I was the first recorder student to be principal study so it was quite a big deal and my teachers were initially Antony Robson and then Peter Holtslag. Peter probably had the most profound impact on my studies and my lessons with him for 3 years were inspiring, educationally and technically challenging but helped to craft my identity as a serious musician who wanted to specialise in the area of early music. By the time I started my Masters degree I had moved across from the modern flute to the baroque flute with Lisa Beznosiuk and never looked back and on graduating from the RAM in 1991 I won the Moeck International Recorder Competition and founded Florilegium.

Can you tell us about the musical education system in the UK? Is there something you would recommend to our recorder students? And on contrary what would you suggest to your UK students from our system?

Reflecting on the musical education system now in the UK compared to when I was a child, which was many, many years ago, I think there are far fewer mainstream opportunities. In the UK I’m afraid music as a core subject in most secondary schools (pupils aged 11-18) has been slipping off the educational radar for some time now and this has had quite a serious effect on the sort of students who I now see coming to the Royal College of Music to audition when they are 18. Recorder of course is taught in some primary schools as a first point of contact with music as the response is immediate but to take this further and with more expert tutoring is quite rare. Those that progress to a significant level tend to be from middle class families, or those who are already attending specialist music schools or the Junior Conservatories in the UK. We are trying hard at the RCM now to engage with communities of young children from disadvantaged backgrounds through various initiatives to encourage music as a fundamental element of everyone’s education. I’m glad to report that we have made some significant positive steps in recent years, so it is not all doom and gloom and I am much more hopeful for the future.

One thing that has always impressed me in my experience in the Czech Republic is how important folk music is to everyone. This seems to have instilled a real love and joy for music in so many people who delight and understand the importance of sharing music together in the way that we simply don’t have in the UK, so we can certainly learn this from you all.

Our educational structures and methods in the UK for musicians wanting to seriously learn the recorder through the private or specialist schools are robust and impressive, and whilst the pool of players coming through to tertiary education might be relatively small, we certainly now audition impressive players with remarkable techniques.

How did it happen that you play both baroque flute and recorder? Did you always want to combine these two instruments? Is there something you really like about flute and recorder?

As I mentioned earlier, I studied both modern flute and recorder as a BMus student at the Royal Academy of Music and was quite happy having both side by side. It was after attending the baroque course in Casa Mateus in northern Portugal that I first tried a baroque flute. I was there as a recorder student of Peter Holtslag and he had been trying to convince me to play the baroque flute for the entire year at the RAM. I complained that it basically didn’t work, was out of tune, made a poor and dull sound and was weak in the bottom register. So one afternoon he took a pair of baroque flutes that he had with him, a couple of bottles of wine from the cellar there and I joined him in the Chapel that was attached to the Palace. We spent all afternoon playing flute duets, all the time he helped me get to grips with the sound world and fingerings of the baroque flute. Of course, the situation was magical. The sun was setting towards the end of the session, casting its golden rays through the beautiful stained-glass windows so how could I not be inspired and transported by this experience.

In fact, by the end of the weeklong course I gave my first ever public performance on the baroque flute in the student concert. I even remember the Telemann cantata we performed from Der Harmonisches Gottesdient, with Peter Gritton (counter tenor and brother of the famous soprano Susan Gritton), and none other than Richard Egarr on harpsichord.

Being a professional flute and recorder player has been so satisfying for me. I find that both instruments work incredibly well side by side. Of course, they both require mastery of certain similar techniques including breathing and finger control, flexibility and versatility of articulation so they complement each other very well. The repertoire for both instruments overlap in baroque music of course, but otherwise the recorder can explore very early and contemporary music whilst the flute is happy in the classical and romantic repertoire, thus giving the performer over 500 years of music to explore over a lifetime.

You often have a chance to play on historical instruments. Can you say something about those you have played? Was there any particularly special for you? I’m sure you have many stories behind while playing or doing recordings on them. Would you like to share some with us?

As a student at the RAM I remember visiting the RCM museum of instruments and being allowed to play the beautiful ivory Denner recorder for 3 minutes. This experience was transformational for me and although I see this beautiful instrument in our Museum almost every day when I am at work at RCM, I have not been allowed to play it ever since.

My story and journey with historical flutes however has been very different and I have been incredibly fortunate to have had some wonderful opportunities in recent years. Firstly, I enjoyed playing a recital on an ivory Stanesby flute (1720) in the collection of historical instruments at Yale University in America. Then for my recording of Telemann solo fantasias I was given permission by the British Royal Family to use a porcelain and gold flute that once belonged to King George IlI of England. In this short film I explain in detail about this unique flute:

https://www.facebook.com/royalcollectiontrust/videos/875840132575539/

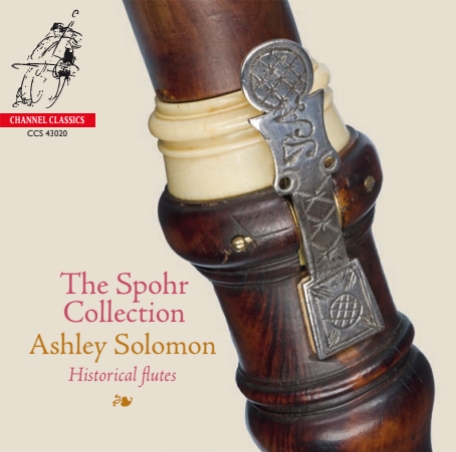

However, over the last few years I have been very lucky to have access to a unique collection of original flutes in Germany owned by Peter Spohr. His flute collection numbers over 600 original instruments. I was fortunate to be allowed to record a cd using 9 of these unique and rare instruments including the earliest playable French flute from the 1680s by Chattillion. We chose the beautiful key on this flute for the front cover of this first volume . I am just planning my second cd using 6 more of his flutes for a recording in January next year.

You are the professor and Head of the Historical Performance Department at the Royal College of Music in London. From my experience this school has a lot to offer to young musicians, but is there something special why you would recommend them to study there?

have been teaching recorder at the RCM since 1994 and have been Head of Historical Performance since 2006 so have spent more than half my life at this institution. I think over the years we have crafted an exceptional education for our students, not just because our 1-1 professors are outstanding leaders in their field but because we embrace a much more holistic approach to teaching. It is important to contextualise your studies, to understand the importance of being not just historically informed but also culturally informed so that all performances have a relevance and context which connects the musicians to the music in a meaningful way.

We also have numerous performing opportunities not just at the institution but across the UK and further afield in Europe, the Americas and even Australia. Our Museum of Instruments and Collections of Manuscripts often drive our research activities and by promoting a culture of theory and practice our musicians have a depth of experience and understanding that is often quite rare these days.

Geographically we are based in a very special area of London known as the Albertopolis, which is a place where science, music, academia and art all meet. This was the original vision of Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert who established several major institutions including the Royal College of Music, the Royal College of Art, The Victoria and Albert Museum, the Natural History Museum, the Science Museum and Imperial College all very close together to inspire and challenge those involved in each place.

In your carrier you often travel and give masterclasses worldwide. Is there a topic that you find extremely interesting, and you like to work on (certain repertoire, musical period etc.)? Do you have some funny stories or exciting moments from your travels?

Most periods of music fascinate me in one way or another and so this is a really tough question to offer a simple answer. I feel especially drawn to all areas of baroque music of course as I spend my life inhabiting this period of musical history. If I had to select a specific composer or style of music then I think it would have to be French baroque music which can be so simple and expressive (Philidor and Hotteterre), but also so incredibly challenging and detailed (Couperin and Rameau). It is so often the most complicated to perform well and there are so many subtle details in some of this music that it is not always successfully n egotiated by musicians these days. Italian music from the 17th and 18th centuries is so much more accessible for most people and instantly gratifying to play on one level, but that is certainly not enough for me.

I also couldn’t ignore the music by Telemann (solo, chamber and orchestral) and Johann Sebastian Bach whose music has the perfect blend of spirituality and intelligence.

There are so many stories from my touring life over the last 30 years with Florilegium and perhaps one of the most stressful was when we were on tour in South America and had just arrived in Rosario in Argentina. There was a message from the concert promoter to inform us that he was sending a car over to our hotel to collect the harpsichord that we had brought with us. Of course, we never travelled there with a harpsichord and for the whole 3-week tour each promoter provided us with an appropriate harpsichord to use for each concert. This particular promoter had decided that we had brought our own keyboard like in the photo that we were using at the time. In it, Neal Peres da Costa is holding the remains of a rotten keyboard. He simply assumed this was the one we would play in concert.

What is your favourite solo repertoire or music which you always enjoy playing on recorder or flute? Which project in your solo career you value the most?

I have always enjoyed the solo works of the recorder virtuoso and bell ringer Jakob van Eyck for sheer excitement, virtuosity and freedom of rhetoric and articulation that this music allows the performer to engage with. In addition, Telemann’s Fantasias have lived with me for most of my playing life and I still really enjoy performing these 12 little gems.

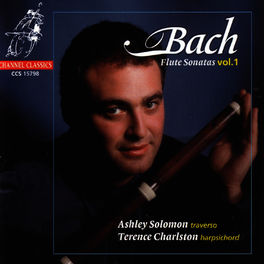

It is impossible to think about a single project that I value above all others in my solo career but perhaps the most meaningful was the recording I made just before I turned 30 of the complete Bach flute sonatas with Terence Charlston.

I had decided after a very serious life-threatening accident when I was 19 that my short-term goal, should I ever be able to play again, something my hand surgeon would not guarentee, was to record these sonatas by the time I was 30. This was mostly a motivational aspiration but, in the end, became reality when Channel Classics offered me a solo recording contract and we recorded these sonatas in 1998. I am certainly very proud of these two cds and when Gramophone Magazine voted in 2017 that my recording with Terence was their favourite recording of these works on either modern or baroque flute from all recordings of these works it felt particularly poignant.

Solomon’s luminous tone and unfussy command of the complicated melodies conflate into something utterly beautiful. Slow movements are soulful in their infinite variety, fast ones are clever and with a wealth of invention behind them. (Gramophone Magazine 2017)

Your ensemble Florilegium, where you are the director, was founded in 1991? I’m sure you have many exciting experiences after such long time. Would you like to share some with us? Or which projects with Florilegium were the most special for you? What are your plans in the future?

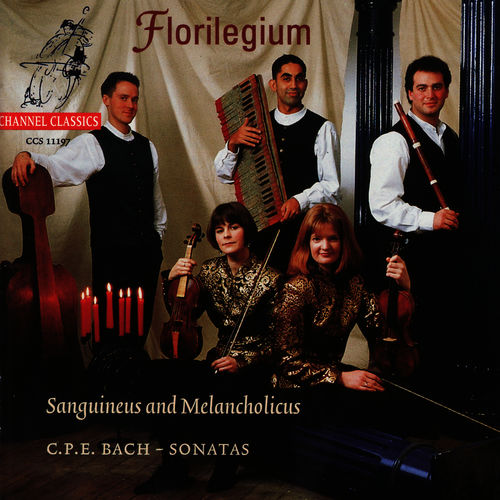

I set up Florilegium with my friend and colleague Neal Peres da Costa in 1991 at a time when there were quite a lot of musicians graduating from the various Conservatoires in London, none of whom had any work. We had spent years playing chamber music together as students and decided that there were enough exceptional players around to form a chamber orchestra initially and then we scaled down to a chamber ensemble of 7 players, including Rachel Podger on the violin. Our first concert was so exciting on 13 July 1991 in Blackheath Concert Halls in London. We programmed far too much music and the concert almost lasted 3 hours, so we had quite a lot to learn about programming, but we just wanted to share all our favourite pieces in this opening debut concert. That was a long time ago and since our debut we have given nearly 1,700 concerts, recorded over 30 cds for Channel Classics, many of which have won awards and I have been fortunate to share these concerts with some of the most outstanding musicians and colleagues.

I will one day write a book of anecdotes about the ensemble and our life on the road and our recording experiences. There are so many stories to share, some good, some traumatic and some almost unbelievable. However, perhaps here I might share how we secured our recording contract with Channel Classics back in 1992, which has been the most wonderful relationship over the years. Our discography with them really does tell the history of Florilegium through the years as we have evolved and matured.

After our debut concert we decided to record 1 piece as a demo to send to all independent record companies. We selected Telemann’s Concerto a 4 in a minor with that incredibly virtuosic last movement with solos for the recorder, oboe and violin. In those days you made a cassette and sent it off in the post with an accompanying letter (gosh I sound old fashioned don’t I!). The cassette found its way to the Dutch producer Ted Diehl who lost the accompanying letter with our contact details. We had forgotten to write any of these details on the actual cassette. This was long before emails and mobile phones. As he had no way of contacting us, he had given up on finding out who we were when he was cleaning his flat one night and discovered our letter had fallen behind his desk. I had a call at midnight from him and by the end of the week he had flown over to meet us, and we were planning our first cd which we recorded in Germany within 3 months. This went on to win the Diapason d’Or and Choc de la Musique in France and our careers were launched.

I would like to ask you about your project in Bolivia. How did this all start, what was the purpose of the project and was it difficult to keep it doing? I remember once I went to the concert at the Royal College of Music where you invited the Bolivian choir, and it was one of the most special concerts in my life! Was it hard work to achieve such high level or easy one because the musicians were very talented?

For Florilegium it all started in 2002 when we were invited to participate in the International Festival of Renaissance and Baroque Music in Bolivia held biennially in the mission churches in the Bolivian jungle. The condition of participation in this festival was that 5-10 minutes of Bolivian Baroque music had to be included in the ensemble’s programme. As the first English group to perform in this Festival, we were amazed by the reception we received from the local audiences, who were almost exclusively indigenous Indians. They were enthusiastic at hearing an English ensemble performing not just European baroque music but also Mission Baroque, music from their Chiquitos and Moxos archives.

Following this unique experience, we promoted an entire programme of Bolivian baroque music at London’s Wigmore Hall the following year. The four soloists joining Florilegium for this production of sacred and secular works from the archives in Bolivia included Dame Emma Kirkby. Following the performance I met with the Director of the Dutch Prince Claus Fund who had attended the Wigmore Hall concert and who was very keen to support this initiative. However, there needed to be a stronger Bolivian involvement in this project and so we discussed the possibility of replacing the English singers with four Bolivian soloists for future projects. I then commuted to Bolivia to work with 4 chosen soloists for the next project. This project continued to evolve and I founded Arakaendar Bolivia Choir in 2005 and then Arakaendar Bolivia baroque orchestra in 2010, all with the expectation to promote music from the archives in the Mission Churches which had been kept hidden for more than 2 centuries after the expulsion of the Jesuits from the Missions in 1767. We have now recorded 3 cds of music on Channel Classics from these archives and the choir have gained a reputation as one of the most exciting and impressive choirs across Latin America.

Here they are performing Fuera Fuera: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZNeYBdGN7OQ

We have toured together throughout Europe and Asia as well as north and south America and I am immensely proud of them all. For more information do follow this link: http://www.florilegium.org.uk/bolivian-diary/

Some years you taught at the Early Music Summer School in Prachatice. Did you enjoy that time? Do you have nice memories that you would like to share with us? Do you have many friends in the Czech Republic. Is there something that you like about the Czech Republic? Such as great beer or talented students 😉

Obviously, I have many fond memories of the courses in Bechyne and also Prachatice over the years. I think the first time we went to teach was in 1994 and we returned on and off for nearly 20 years or more, giving concerts as well as masterclasses for so many wonderful musicians from the Czech Republic and further afield. This has led to many lifelong friendships and experiences that I still think of fondly today. The fireflies by the river in Bechyne, arriving at the Bakery at 04.00 to buy fresh bread straight from the oven, the dark beer and the Tower Restaurant in Prachatice that made the best steak I had ever eaten. Then there were the lectures and classes and teachers of not just recorder, but also voice, strings etc and the chamber music sessions that went on through the night sometimes. It was a very special time with very special and talented students, many of whom have good careers now. And then the final night of the course when we would have a long student concert followed by drinking, eating and hours of Czech folk songs until the sun would rise and we would ironically sing “dobrou noc”, a lullaby that I then started to sing to my young children when putting them to bed each night in London. Very special times indeed. I miss the courses hugely but appreciate the friendships that flourished each summer because of these weeks together in south Bohemia.

It’s probably hard question, but how many instruments do you have? Are there any that you value the most?

I have over 40 recorders and 25 flutes and it is difficult to select favourites. Perhaps from my recorders I love those made for me by Mike Grinter in Australia (Bressan alto, Ganassi sopranos and G altos and my Bressan voice flute). Of all the flutes I have I think my Cameron copy of the famous Denner flute that was discovered when the Berlin wall came down is the most special instrument and the one I used for my Bach sonatas cd back in 1998. For my recent Spohr Collection CD I was allowed to use the original Denner flute that my copy was modelled on, which is now in this private collection and I used it to record my arrangement of Bach’s Organ Trio Sonata BWV 525 for flute and harpsichord.

You are very successful and busy musician, but it’s not easy to start a musical career. Is there something that you would suggest to recorder students at the start of their musical career?

There are no short cuts to a successful and long career in music. You have to be passionate about it and not want to do anything else as it really is a tough career choice. The most important attributes I think include being humble, loving the repertoire and always looking for sources of inspiration. Of course, you must be prepared to work really hard, be self-critical and continue to always search for technical perfection and musical satisfaction.

Do you like contemporary recorder music? Are there any contemporary projects, recorder players or composers you find inspirational?

I certainly don’t object to contemporary music and in the past have enjoyed certain pieces that became staples of my repertoire including works by Berio, Ishii, Stockhausen, Andriessen and Shinohara. I have dabbled in more recent works too by McGowan, Tedde and Yun), but feel that I cannot devote enough time to this music to really justify it becoming a main part of my core repertoire. From a teaching perspective I appreciate my limitations here and appointed the wonderful Julien Feltrin many years ago to teach our students at RCM all of this contemporary repertoire with live electronics as well. As a result of his exceptional teaching our students can all circular breathe and perform some of the most challenging repertoire amazingly well. I am full of admiration for what they manage to present in their recitals and examinations.

Please can you tell us something about your future plans? And also how is Ashley Solomon enjoying his free time? If there is any.

Future plans are exciting now that live concerts are returning post covid and we are planning complete programmes of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerti, Bach’s Musical Offering, chamber works by Couperin (Les Nations), a series of concerts of Telemann’s Paris Quartets and Tafelmusik and works by Pergolesi, Scarlatti and Handel. In addition were are recording a CD of Haydn’s early symphonies Morning, Noon and Night for Channel Classics in March next year as well as Spohr Collection volume 2 where I will be recording concerti by Vivaldi, CPEBach, Quantz, Blavet, Buffardin and Woodcock. I will also be directing a number of new programmes in Bolivia with Arakaendar Bolivia Choir and Orchestra, which we also hope to tour through Europe towards the end of 2022.

Free time – what’s free time? Ah well my biggest distraction in the newest member of our family – Kiki our border collie who is nearly 2 years old.

The interview was prepared by Ilona Veselovská and Václav Bratrych